Kingdom of France

Kingdom of France

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

The Kingdom of France (French: Royaume de France) was a medieval and early modern monarchy in Western Europe. It was one of the most powerful states in Europe and a great power since the Late Middle Ages and the Hundred Years' War. It was also an early colonial power, with possessions around the world.

France originated as West Francia (Francia Occidentalis), the western half of the Carolingian Empire, with the Treaty of Verdun (843). A branch of the Carolingian dynasty continued to rule until 987, when Hugh Capet was elected king and founded the Capetian dynasty. The territory remained known as Francia and its ruler as rex Francorum ("king of the Franks") well into the High Middle Ages. The first king calling himself Roi de France ("King of France") was Philip II, in 1190. France continued to be ruled by the Capetians and their cadet lines—the Valois and Bourbon—until the monarchy was overthrown in 1792 during the French Revolution.

France in the Middle Ages was a de-centralised, feudal monarchy. In Brittany and Catalonia (now a part of Spain) the authority of the French king was barely felt. Lorraine and Provence were states of the Holy Roman Empire and not yet a part of France. Initially, West Frankish kings were elected by the secular and ecclesiastic magnates, but the regular coronation of the eldest son of the reigning king during his father's lifetime established the principle of male primogeniture, which became codified in the Salic law. During the Late Middle Ages, the Kings of England laid claim to the French throne, resulting in a series of conflicts known as the Hundred Years' War (1337–1453). Subsequently, France sought to extend its influence into Italy, but was defeated by Spain in the ensuing Italian Wars (1494–1559).

France in the early modern era was increasingly centralised; the French language began to displace other languages from official use, and the monarch expanded his absolute power, albeit in an administrative system (the Ancien Régime) complicated by historic and regional irregularities in taxation, legal, judicial, and ecclesiastic divisions, and local prerogatives. Religiously France became divided between the Catholic majority and a Protestant minority, the Huguenots, which led to a series of civil wars, the Wars of Religion (1562–1598). France laid claim to large stretches of North America, known collectively as New France. Wars with Great Britain led to the loss of much of this territory by 1763. French intervention in the American Revolutionary War helped secure the independence of the new United States of America.

The Kingdom of France adopted a written constitution in 1791, but the Kingdom was abolished a year later and replaced with the First French Republic. The monarchy was restored by the other great powers in 1814 and lasted (except for the Hundred Days in 1815) until the French Revolution of 1848.

| Kingdom of France | ||||||||||||||

| Royaume de France | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| Motto Montjoie Saint Denis! | ||||||||||||||

| Anthem Marche Henri IV (1590–1792,1814–1830) "March of Henry IV" "The Parisian" | ||||||||||||||

|

The Kingdom of France in 1789.

| ||||||||||||||

| Capital |

| |||||||||||||

| Languages | ||||||||||||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism | |||||||||||||

| Government |

| |||||||||||||

| King | ||||||||||||||

| • | 987–996 | Hugh Capet | ||||||||||||

| • | 1180–1223 | Philip II | ||||||||||||

| • | 1364–1380 | Charles V | ||||||||||||

| • | 1422–1461 | Charles VII | ||||||||||||

| • | 1589–1610 | Henry IV | ||||||||||||

| • | 1643–1715 | Louis XIV | ||||||||||||

| • | 1774–1792 | Louis XVI | ||||||||||||

| • | 1814–1824 | Louis XVIII | ||||||||||||

| • | 1824–1830 | Charles X | ||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | ||||||||||||||

| • | 1815 | Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand | ||||||||||||

| • | 1847–1848 | François Guizot | ||||||||||||

| Legislature |

| |||||||||||||

| • | Upper house | Chamber of Peers | ||||||||||||

| • | Lower house | Chamber of Deputies | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | Medieval / Early Modern | |||||||||||||

| • | Begin of Capetian dynasty | 3 July 987 | ||||||||||||

| • | Hundred Years' War | 1337–1453 | ||||||||||||

| • | French Wars of Religion | 1562–1598 | ||||||||||||

| • | French Revolution | 5 May 1789 | ||||||||||||

| • | Bourbon Restoration | 6 April 1814 | ||||||||||||

| • | Bourbon Monarchy Deposed | 2 August 1830 | ||||||||||||

| • | July Monarchy deposed | 24 February 1848 | ||||||||||||

| Currency | Livre, Franc, Écu, Louis d'or | |||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| Today part of | ||||||||||||||

France originated as West Francia (Francia Occidentalis), the western half of the Carolingian Empire, with the Treaty of Verdun (843). A branch of the Carolingian dynasty continued to rule until 987, when Hugh Capet was elected king and founded the Capetian dynasty. The territory remained known as Francia and its ruler as rex Francorum ("king of the Franks") well into the High Middle Ages. The first king calling himself Roi de France ("King of France") was Philip II, in 1190. France continued to be ruled by the Capetians and their cadet lines—the Valois and Bourbon—until the monarchy was overthrown in 1792 during the French Revolution.

France in the Middle Ages was a de-centralised, feudal monarchy. In Brittany and Catalonia (now a part of Spain) the authority of the French king was barely felt. Lorraine and Provence were states of the Holy Roman Empire and not yet a part of France. Initially, West Frankish kings were elected by the secular and ecclesiastic magnates, but the regular coronation of the eldest son of the reigning king during his father's lifetime established the principle of male primogeniture, which became codified in the Salic law. During the Late Middle Ages, the Kings of England laid claim to the French throne, resulting in a series of conflicts known as the Hundred Years' War (1337–1453). Subsequently, France sought to extend its influence into Italy, but was defeated by Spain in the ensuing Italian Wars (1494–1559).

France in the early modern era was increasingly centralised; the French language began to displace other languages from official use, and the monarch expanded his absolute power, albeit in an administrative system (the Ancien Régime) complicated by historic and regional irregularities in taxation, legal, judicial, and ecclesiastic divisions, and local prerogatives. Religiously France became divided between the Catholic majority and a Protestant minority, the Huguenots, which led to a series of civil wars, the Wars of Religion (1562–1598). France laid claim to large stretches of North America, known collectively as New France. Wars with Great Britain led to the loss of much of this territory by 1763. French intervention in the American Revolutionary War helped secure the independence of the new United States of America.

The Kingdom of France adopted a written constitution in 1791, but the Kingdom was abolished a year later and replaced with the First French Republic. The monarchy was restored by the other great powers in 1814 and lasted (except for the Hundred Days in 1815) until the French Revolution of 1848.

Contents

Political history

West Francia

During the later years of the elderly Charlemagne's rule, the Vikings made advances along the northern and western perimeters of the Kingdom of the Franks. After Charlemagne's death in 814 his heirs were incapable of maintaining political unity and the empire began to crumble. The Treaty of Verdun of 843 divided the Carolingian Empire into three parts, with Charles the Bald ruling over West Francia, the nucleus of what would develop into the kingdom of France.[1] Charles the Bald was also crowned King of Lotharingia after the death of Lothair II in 869, but in the Treaty of Meerssen (870) was forced to cede much of Lotharingia to his brothers, retaining the Rhone and Meuse basins (including Verdun, Vienne and Besançon) but leaving the Rhineland with Aachen, Metz and Trier in East Francia.Viking advances were allowed to increase, and their dreaded longships were sailing up the Loire and Seine rivers and other inland waterways, wreaking havoc and spreading terror. During the reign of Charles the Simple (898–922), Normans under Rollo from Norway, were settled in an area on either side of the River Seine, downstream from Paris, that was to become Normandy.[2][3]

High Middle Ages

The Carolingians were to share the fate of their predecessors: after an intermittent power struggle between the two dynasties, the accession in 987 of Hugh Capet, Duke of France and Count of Paris, established the Capetian dynasty on the throne. With its offshoots, the houses of Valois and Bourbon, it was to rule France for more than 800 years.[4]The old order left the new dynasty in immediate control of little beyond the middle Seine and adjacent territories, while powerful territorial lords such as the 10th- and 11th-century counts of Blois accumulated large domains of their own through marriage and through private arrangements with lesser nobles for protection and support.

The area around the lower Seine became a source of particular concern when Duke William took possession of the kingdom of England by the Norman Conquest of 1066, making himself and his heirs the King's equal outside France (where he was still nominally subject to the Crown).

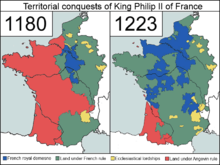

Henry II inherited the Duchy of Normandy and the County of Anjou, and married France's newly divorced ex-queen, Eleanor of Aquitaine, who ruled much of southwest France, in 1152. After defeating a revolt led by Eleanor and three of their four sons, Henry had Eleanor imprisoned, made the Duke of Brittany his vassal, and in effect ruled the western half of France as a greater power than the French throne. However, disputes among Henry's descendants over the division of his French territories, coupled with John of England's lengthy quarrel with Philip II, allowed Philip II to recover influence over most of this territory. After the French victory at the Battle of Bouvines in 1214, the English monarchs maintained power only in southwestern Duchy of Guyenne.[5]

Late Middle Ages and the Hundred Years' War

France in 1223

The losses of the century of war were enormous, particularly owing to the plague (the Black Death, usually considered an outbreak of bubonic plague), which arrived from Italy in 1348, spreading rapidly up the Rhone valley and thence across most of the country: it is estimated that a population of some 18–20 million in modern-day France at the time of the 1328 hearth tax returns had been reduced 150 years later by 50 percent or more.[7]

Renaissance and Reformation

The Renaissance era was noted for the emergence of powerful centralized institutions, as well as a flourishing culture ( much of it imported from Italy).[8] The kings built a strong fiscal system, which heightened the power of the king to raise armies that overawed the local nobility.[9] In Paris especially there emerged strong traditions in literature, art and music. The prevailing style was classical.[10][11]The Ordinance of Villers-Cotterêts was signed into law by Francis I in 1539. Largely the work of Chancellor Guillaume Poyet, it dealt with a number of government, judicial and ecclesiastical matters. Articles 110 and 111, the most famous, called for the use of the French language in all legal acts, notarised contracts and official legislation.

Italian Wars

After the Hundred Years' War, Charles VIII of France signed three additional treaties with Henry VII of England, Maximilian I of Habsburg, and Ferdinand II of Aragon respectively at Étaples (1492), Senlis (1493) and in Barcelona (1493). These three treaties cleared the way for France to undertake the long Italian Wars (1494–1559), which marked the beginning of early modern France. French efforts to gain dominance resulted only in the increased power of the Habsburg house.Wars of Religion

Henry IV, by Frans Pourbus the younger, 1610.

The Wars of Religion culminated in the War of the Three Henrys in which Henry III assassinated Henry de Guise, leader of the Spanish-backed Catholic league, and the king was murdered in return. After the assassination of both Henry of Guise (1588) and Henry III (1589), the conflict was ended by the accession of the Protestant king of Navarre as Henry IV (first king of the Bourbon dynasty) and his subsequent abandonment of Protestantism (Expedient of 1592) effective in 1593, his acceptance by most of the Catholic establishment (1594) and by the Pope (1595), and his issue of the toleration decree known as the Edict of Nantes (1598), which guaranteed freedom of private worship and civil equality.[13]

Early Modern period

Colonial France

Louis XIII, by Philippe de Champaigne, 1647.

Thirty Years' War

Henry IV's son Louis XIII and his minister (1624–1642) Cardinal Richelieu, elaborated a policy against Spain and the Holy Roman Empire during the Thirty Years' War (1618–48) which had broken out in Germany. After the death of both king and cardinal, the Peace of Westphalia (1648) secured universal acceptance of Germany's political and religious fragmentation, but the Regency of Anne of Austria and her minister Cardinal Mazarin experienced a civil uprising known as the Fronde (1648–1653) which expanded into a Franco-Spanish War (1653–59). The Treaty of the Pyrenees (1659) formalised France's seizure (1642) of the Spanish territory of Roussillon after the crushing of the ephemeral Catalan Republic and ushered a short period of peace.[14]Administrative structures

Provinces in 1789.

Louis XIV, the Sun King

Louis XIV, by Hyacinthe Rigaud, 1701

The king sought to impose total religious uniformity on the country, repealing the "Edict of Nantes" in 1685. The infamous practice of "dragonnades" was adopted, whereby intentionally rough soldiers were quartered in the homes of Protestant families and allowed to have their way with them — stealing, raping, torturing and killing adults and infants in their hovels. It is estimated that anywhere between 150,000 and 300,000 Protestants fled France during the wave of persecution that followed the repeal,[17] [18], (following "Huguenots" beginning a hundred and fifty years earlier until the end of the 18th Century) costing the country a great many intellectuals, artisans, and other valuable people. Persecution extended to unorthodox Roman Catholics like the Jansenists, a group that denied free will and had already been condemned by the popes. Louis was no theologian and understood little of the complex doctrines of Jansenism, satisfying himself with the fact that they threatened the unity of the state. In this, he garnered the friendship of the papacy, which had previously been hostile to France because of its policy of putting all church property in the country under the jurisdiction of the state rather than that of Rome.[19]

In November 1700, the Spanish king Charles II died, ending the Habsburg line in that country. Louis had long waited for this moment, and now planned to put a Bourbon relative, Philip, Duke of Anjou, (1683–1746), on the throne. Essentially, Spain was to become a perpetual ally and even obedient satellite of France, ruled by a king who would carry out orders from Versailles. Realizing how this would upset the balance of power, the other European rulers were outraged. However, most of the alternatives were equally undesirable. For example, putting another Habsburg on the throne would end up recreating the grand multi-national empire of Charles V (1500–58), of the Holy Roman Empire (German First Reich), Spain, and the Two Sicilies which would also grossly upset the power balance. After nine years of exhausting war, the last thing Louis wanted was another conflict. However, the rest of Europe would not stand for his ambitions in Spain, and so the long War of the Spanish Succession began (1701–14), a mere three years after the War of the Grand Alliance, (1688–97, aka "War of the League of Augsburg") had just concluded.[20]

Louis XV, by Hyacinthe Rigaud, 1730

Dissent and revolution

The reign (1715–74) of Louis XV saw an initial return to peace and prosperity under the regency (1715–23) of Philippe II, Duke of Orléans, whose policies were largely continued (1726–1743) by Cardinal Fleury, prime minister in all but name. The exhaustion of Europe after two major wars resulted in a long period of peace, only interrupted by minor conflicts like the War of the Polish Succession from 1733–35. Large-scale warfare resumed with the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–48). But alliance with the traditional Habsburg enemy (the "Diplomatic Revolution" of 1756) against the rising power of Britain and Prussia led to costly failure in the Seven Years' War (1756–63) and the loss of France's North American colonies.[21]On the whole, the 18th century saw growing discontent with the monarchy and the established order. Louis XV was a highly unpopular king for his sexual excesses, overall weakness, and for losing Canada to the British. A strong ruler like Louis XIV could enhance the position of the monarchy, while Louis XV weakened it. The writings of the philosophes such as Voltaire were a clear sign of discontent, but the king chose to ignore them. He died of smallpox in 1774, and the French people shed few tears at his passing. While France had not yet experienced the Industrial Revolution that was beginning in Britain, the rising middle class of the cities felt increasingly frustrated with a system and rulers that seemed silly, frivolous, aloof, and antiquated, even if true feudalism no longer existed in France.

Louis XVI, by Antoine-François Callet, 1775

With the country deeply in debt, Louis XVI permitted the radical reforms of Turgot and Malesherbes, but noble disaffection led to Turgot's dismissal and Malesherbes' resignation in 1776. They were replaced by Jacques Necker. Necker had resigned in 1781 to be replaced by Calonne and Brienne, before being restored in 1788. A harsh winter that year led to widespread food shortages, and by then France was a powder keg ready to explode.[23] On the eve of the French Revolution of July 1789, France was in a profound institutional and financial crisis, but the ideas of the Enlightenment had begun to permeate the educated classes of society.[24]

Limited monarchy

On September 3, 1791, the absolute monarchy which had governed France for 948 years was forced to limit its power and become a provisional constitutional monarchy. However, this too would not last very long and on September 21, 1792 the French monarchy was effectively abolished by the proclamation of the French First Republic. The role of the King in France in a Revolution gone berserk, was finally brought to a shattering end with the "guillotined" execution (beheading) in the public square of the "Place de la Revolution" of Louis XVI on Monday, January 21, 1793, which was followed by the infamous "Reign of Terror", mass executions and the provisional "Directory" form of republican government, and the eventual beginnings of twenty-five years of reform, upheaval, dictatorship, wars and renewal, with the various Napoleonic Wars.Restoration

Louis XVIII by Robert Lefèvre (1822)

Charles X by Thomas Lawrence (1825)

When a Seventh European Coalition deposed Napoleon after the Battle of Waterloo in 1815, the Bourbon monarchy was once again restored. The Count of Provence, brother of the Louis XVI, who was guillotined in 1793, was crowned as Louis XVIII, nicknamed "The Desired". Louis XVIII tried to conciliate the legacies of the Revolution and Ancien Régime both, also permitting the formation of a Parliament and constitutional Charter, usually "Charte octroyée" ("Granted Charter"). His reign was characterized by disagreements between the Doctrinaires, liberal thinkers who supported the Charter and rising bourgeoisie, and the Ultra-royalists, aristocrats and clergymen who totally refused the Revolution's heritage. However, the peace was granted by and statesmen like Talleyrand and the Duke of Richelieu, as well as King's moderation and prudent intervention.[25][26] In 1823, the liberal agitations in Spain brought to a French intervention on the royalist's side, who permitted to King Ferdinand VII to reject the Constitution.[clarification needed]

However, the work of Louis XVIII was frustrated when, after his death in 16 September 1824, his brother the Count of Artois became King under the name of Charles X. Charles X was a strong reactionary who supported ultra-royalists and Catholic Church. Under his reign, the censorship of newspapers was reinforced, the Anti-Sacrilege Act passed and compensations to French Émigré were increased. However, there were also the intervention in the Greek Revolution and the first phase of the conquest of Algeria.

The absolutist tendencies of the King were disliked by Doctrinaire majority in the Chamber of Deputies, that in 18 March 1830 sent and cordial address to the King, remembering to him his vote on the Charter. However, Charles X received this address as a veiled threat, and in 25 July of the same year, he emanated the St. Cloud Ordinances, a plot to reduce Parliament powers and re-establish absolute rule.[27] The opposition reacted with riots in Parliament and barricades in Paris, that erupteds in the July Revolution.[28] The King abdicated, such as his son the Prince Louis Antoine, in favour to his grandson Count of Chambord, nominating his cousin the Duke of Orléans as regent.[29] However, it was too late, and the liberal opposition won over the monarchy.

Aftermath and July Monarchy

Louis Philippe I by François Gérard (1834)

However, despite the initial reforms, Louis Philippe was little different than his predecessors. The old nobility was replaced by urban bourgeoisie, and the working class was excluded from voting.[33] Louis Philippe appointed notable bourgeois as Prime Minister, like banker Casimir Périer, academic François Guizot, general Jean-de-Dieu Soult, and thus obtained the nickname of "Citizen King" (Roi Bourgeois). The July Monarchy was beset by corruption scandals and financial crisis. The opposition of the King was composed of Legitimists, supporting the Count of Chambord, Bourbon claimant to the Throne, and of Bonapartists and Republicans who fought against royalty and supported the principles of democracy. The King tried to suppress the opposition with censorship, but when the Campagne des banquets ("Banquets' Campaign") was repressed in February 1848,[34] riots and seditions erupted in Paris and later all France, resulting in the February Revolution. The National Guard refused to repress the rebellion, resulting in Louis Philippe abdicating and fleeing to England. On 24 February 1848, the monarchy was abolished and the Second Republic was proclaimed.[35] Despite later attempts to re-establish the Kingdom in the 1870s, during the Third Republic, the original French monarchy never returned.

Territories and provinces

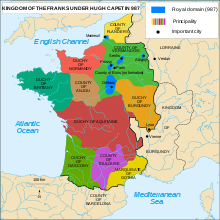

Western Francia during the time of Hugh Capet. The royal domain is shown in blue

The kingdom of France in 1030 (royal domain in light blue)

Territorial development under Philip August (Philip II), 1180–1223

Territories inherited from Western Francia:

Domain of the Frankish king (royal domain or demesne, see Crown lands of France)

Domain of the Frankish king (royal domain or demesne, see Crown lands of France)

- Direct vassals of the French king in the 10th to 12th centuries:

County of Champagne (to the royal domain in 1316)

County of Champagne (to the royal domain in 1316) County of Blois (to the royal domain in 1391)

County of Blois (to the royal domain in 1391) Duchy of Burgundy (until 1477, then divided between France and the Habsburgs)

Duchy of Burgundy (until 1477, then divided between France and the Habsburgs) County of Flanders (to Burgundy in 1369)

County of Flanders (to Burgundy in 1369) Duchy of Bourbon (1327–1523)

Duchy of Bourbon (1327–1523)

- Duchy of Normandy (1204)

- County of Tourain (1204)

- County of Anjou (1225)

- County of Maine (1225)

- County of Auvergne (1271)

County of Toulouse (1271), including:

County of Toulouse (1271), including:

- County of Quercy

- County of Rouergue

- County of Gevaudan

- Viscounty of Albi

- Marquisat of Gothia

County of Champagne (to the royal domain in 1316)

County of Champagne (to the royal domain in 1316) Dauphiné (1349), hereditary possession of the kings of France, to be held by the heir apparent, but technically not part of the kingdom of France because it remained nominally part of the Holy Roman Empire.

Dauphiné (1349), hereditary possession of the kings of France, to be held by the heir apparent, but technically not part of the kingdom of France because it remained nominally part of the Holy Roman Empire. County of Blois (to the royal domain in 1391)

County of Blois (to the royal domain in 1391)

- Duchy of Aquitaine (Guyenne), including:

County of Poitou

County of Poitou County of La Marche

County of La Marche County of Angoulême

County of Angoulême County of Périgord

County of Périgord

- County of Velay

County of Saintonge

County of Saintonge Viscounty of Limousin

Viscounty of Limousin Lordship of Issoudun

Lordship of Issoudun- Lordship of Déols

- Duchy of Gascogne (Gascony)

- County of Agenais

Duchy of Bretagne (disputed since the War of the Breton Succession, to France in 1453, to the royal demesne in 1547)

Duchy of Bretagne (disputed since the War of the Breton Succession, to France in 1453, to the royal demesne in 1547)

Duchy of Burgundy (1477)

Duchy of Burgundy (1477) Pale of Calais (1558)

Pale of Calais (1558) Kingdom of Navarre (1620)

Kingdom of Navarre (1620) Alsace: Peace of Westphalia (1648), Treaty of Nijmegen, Truce of Ratisbon (1684)

Alsace: Peace of Westphalia (1648), Treaty of Nijmegen, Truce of Ratisbon (1684) County of Artois (1659)

County of Artois (1659)- Roussillon and Perpignan, Montmédy and other parts of Luxembourg, parts of Flanders, including Arras, Béthune, Gravelines and Thionville (Treaty of the Pyrenees 1659)

Free County of Burgundy (1668, 1679)

Free County of Burgundy (1668, 1679)- French Hainaut (1679)

Principality of Orange (1713)

Principality of Orange (1713) Duchy of Lorraine (1766)

Duchy of Lorraine (1766)- French conquest of Corsica (1769)

Comtat Venaissin (1791)

Comtat Venaissin (1791)

Comments

Post a Comment