Holy Roman Empire

Holy Roman Empire

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

Latin: Sacrum Romanum Imperium; German: Heiliges Römisches Reich) was a multi-ethnic complex of territories in central Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806.[6] The largest territory of the empire after 962 was the Kingdom of Germany, though it also came to include the Kingdom of Bohemia, the Kingdom of Burgundy, the Kingdom of Italy, and numerous other territories.[7][8][9]

On 25 December 800, Pope Leo III crowned the Frankish king Charlemagne as Emperor, reviving the title in Western Europe, more than three centuries after the fall of the Western Roman Empire. The title continued in the Carolingian family until 888 and from 896 to 899, after which it was contested by the rulers of Italy in a series of civil wars until the death of the last Italian claimant, Berengar, in 924.

The title was revived in 962 when Otto I was crowned emperor, fashioning himself as the successor of Charlemagne[10] and beginning a continuous existence of the empire for over eight centuries.[11][12][13] Some historians refer to the coronation of Charlemagne as the origin of the empire,[14][15] while others prefer the coronation of Otto I as its beginning.[16][17] Scholars generally concur, however, in relating an evolution of the institutions and principles constituting the empire, describing a gradual assumption of the imperial title and role.[8][14]

The precise term "Holy Roman Empire" was not used until the 13th century, but the concept of translatio imperii,[c] the notion that he – the sovereign ruler – held supreme power inherited from the emperors of Rome, was fundamental to the prestige of the emperor.[8] The office of Holy Roman Emperor was traditionally elective, although frequently controlled by dynasties. The mostly German prince-electors, the highest-ranking noblemen of the empire, usually elected one of their peers as "King of the Romans", and he would later be crowned emperor by the Pope; the tradition of papal coronations was discontinued in the 16th century. The empire never achieved the extent of political unification formed in France, evolving instead into a decentralized, limited elective monarchy composed of hundreds of sub-units: kingdoms, principalities, duchies, counties, Free Imperial Cities, and other domains.[9][18] The power of the emperor was limited, and while the various princes, lords, bishops, and cities of the empire were vassals who owed the emperor their allegiance, they also possessed an extent of privileges that gave them de facto independence within their territories. Emperor Francis II dissolved the empire on 6 August 1806, after the creation of the Confederation of the Rhine by Napoleon.

| Holy Roman Empire | ||||||||||||||||||

| Sacrum Romanum Imperium (Latin) Heiliges Römisches Reich (German) | ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

|

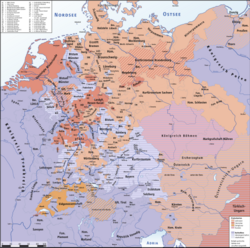

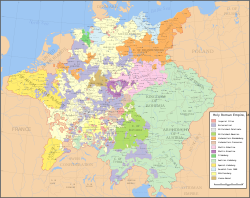

The Holy Roman Empire at its greatest extent during the Hohenstaufen dynasty (1155–1268) superimposed on modern state borders

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Vienna (Reichshofrat from 1497) Regensburg (Reichstag from 1663) Wetzlar (Reichskammergericht from 1689) For other imperial administrative centres, see below. | |||||||||||||||||

| Languages | Latin (administrative/liturgical/ceremonial) Various[b] | |||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism (800–1806) Lutheranism (1555–1806) Calvinism (1648–1806) see details | |||||||||||||||||

| Government | Elective monarchy | |||||||||||||||||

| Emperor | ||||||||||||||||||

| • | 800–814 | Charlemagne[a] | ||||||||||||||||

| • | 962–973 | Otto I (first) | ||||||||||||||||

| • | 1792–1806 | Francis II (last) | ||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Imperial Diet | |||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages Early modern period | |||||||||||||||||

| • | Charlemagne is crowned Emperor of the Romans[a] | 25 December 800 | ||||||||||||||||

| • | Otto I is crowned Emperor of the Romans | 2 February 962 | ||||||||||||||||

| • | Conrad II assumes crown of Burgundy | 2 February 1033 | ||||||||||||||||

| • | Peace of Augsburg | 25 September 1555 | ||||||||||||||||

| • | Peace of Westphalia | 24 October 1648 | ||||||||||||||||

| • | Battle of Austerlitz | 2 December 1805 | ||||||||||||||||

| • | Francis II abdicated | 6 August 1806 | ||||||||||||||||

| Population | ||||||||||||||||||

| • | 1500 est. | 16,000,000[2][3] | ||||||||||||||||

| • | 1618 est. | 21,000,000[4] | ||||||||||||||||

| • | 1648 est. | 16,000,000[4] | ||||||||||||||||

| • | 1786 est. | 26,265,000[5] | ||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

On 25 December 800, Pope Leo III crowned the Frankish king Charlemagne as Emperor, reviving the title in Western Europe, more than three centuries after the fall of the Western Roman Empire. The title continued in the Carolingian family until 888 and from 896 to 899, after which it was contested by the rulers of Italy in a series of civil wars until the death of the last Italian claimant, Berengar, in 924.

The title was revived in 962 when Otto I was crowned emperor, fashioning himself as the successor of Charlemagne[10] and beginning a continuous existence of the empire for over eight centuries.[11][12][13] Some historians refer to the coronation of Charlemagne as the origin of the empire,[14][15] while others prefer the coronation of Otto I as its beginning.[16][17] Scholars generally concur, however, in relating an evolution of the institutions and principles constituting the empire, describing a gradual assumption of the imperial title and role.[8][14]

The precise term "Holy Roman Empire" was not used until the 13th century, but the concept of translatio imperii,[c] the notion that he – the sovereign ruler – held supreme power inherited from the emperors of Rome, was fundamental to the prestige of the emperor.[8] The office of Holy Roman Emperor was traditionally elective, although frequently controlled by dynasties. The mostly German prince-electors, the highest-ranking noblemen of the empire, usually elected one of their peers as "King of the Romans", and he would later be crowned emperor by the Pope; the tradition of papal coronations was discontinued in the 16th century. The empire never achieved the extent of political unification formed in France, evolving instead into a decentralized, limited elective monarchy composed of hundreds of sub-units: kingdoms, principalities, duchies, counties, Free Imperial Cities, and other domains.[9][18] The power of the emperor was limited, and while the various princes, lords, bishops, and cities of the empire were vassals who owed the emperor their allegiance, they also possessed an extent of privileges that gave them de facto independence within their territories. Emperor Francis II dissolved the empire on 6 August 1806, after the creation of the Confederation of the Rhine by Napoleon.

Contents

Name

In various languages the Holy Roman Empire was known as: Latin: Sacrum Romanum Imperium, German: Heiliges Römisches Reich, Italian: Sacro Romano Impero (before Otto I), Italian: Sacro Romano Impero Germanico (by Otto I), Czech: Svatá říše římská, Slovene: Sveto rimsko cesarstvo, Dutch: Heilige Roomse Rijk, French: Saint-Empire romain (before Otto I), French: Saint-Empire romain germanique (by Otto I).[19] Before 1157, the realm was merely referred to as the Roman Empire.[20] The term sacrum ("holy", in the sense of "consecrated") in connection with the medieval Roman Empire was used beginning in 1157 under Frederick I Barbarossa ("Holy Empire"): the term was added to reflect Frederick's ambition to dominate Italy and the Papacy.[21] The form "Holy Roman Empire" is attested from 1254 onward.[22]In a decree following the 1512 Diet of Cologne, the name was changed to the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation (German: Heiliges Römisches Reich der Deutscher Nation, Latin: Imperium Romanum Sacrum Nationis Germanicæ),[23][24] a form first used in a document in 1474.[21] The new title was adopted partly because the Empire had lost most of its Italian and Burgundian (Kingdom of Arles) territories by the late 15th century,[25] but also to emphasize the new importance of the German Imperial Estates in ruling the Empire due to the Imperial Reform.[26] By the end of the 18th century, the term "Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation" had fallen out of official use. Besides, contradicting the traditional view concerning that designation, Hermann Weisert has stated in a study on imperial titulature that, despite the claim of many textbooks, the name Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation never had an official status and points out that documents were thirty times as likely to omit the national suffix as include it.[27]

In a famous assessment of the name, Voltaire remarked sardonically: "This agglomeration which was called and which still calls itself the Holy Roman Empire was in no way holy, nor Roman, nor an empire."[28]

History

Early Middle Ages

Carolingian forerunners

As Roman power in Gaul declined during the 5th century, local Germanic tribes assumed control.[29] In the late 5th and early 6th centuries, the Merovingians, under Clovis I and his successors, consolidated Frankish tribes and extended hegemony over others to gain control of northern Gaul and the middle Rhine river valley region.[30][31] By the middle of the 8th century, however, the Merovingians had been reduced to figureheads, and the Carolingians, led by Charles Martel, had become the de facto rulers.[32] In 751, Martel’s son Pepin became King of the Franks, and later gained the sanction of the Pope.[33][34] The Carolingians would maintain a close alliance with the Papacy.[35]In 768 Pepin’s son Charlemagne became King of the Franks and began an extensive expansion of the realm. He eventually incorporated the territories of present-day France, Germany, northern Italy, and beyond, linking the Frankish kingdom with Papal lands.[36][37]

In 797, the Eastern Roman Emperor Constantine VI was removed from the throne by his mother Irene who declared herself Empress. As the Church regarded a male Roman Emperor as the head of Christendom, Pope Leo III sought a new candidate for the dignity. Charlemagne's good service to the Church in his defense of Papal possessions against the Lombards made him the ideal candidate. On Christmas Day of 800, Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne emperor, restoring the title in the West for the first time in over three centuries.[38][39] In 802, Irene was overthrown by Nikephoros I and henceforth there were two Roman Emperors.

After Charlemagne died in 814, the imperial crown passed to his son, Louis the Pious. Upon Louis' death in 840, it passed to his son Lothair, who had been his co-ruler. By this point the territory of Charlemagne had been divided into several territories, and over the course of the later ninth century the title of Emperor was disputed by the Carolingian rulers of Western Francia and Eastern Francia, with first the western king (Charles the Bald) and then the eastern (Charles the Fat), who briefly reunited the Empire, attaining the prize.[citation needed] After the death of Charles the Fat in 888, however, the Carolingian Empire broke apart, and was never restored. According to Regino of Prüm, the parts of the realm "spewed forth kinglets", and each part elected a kinglet "from its own bowels".[40] After the death of Charles the Fat, those crowned emperor by the pope controlled only territories in Italy.[citation needed] The last such emperor was Berengar I of Italy, who died in 924.

Formation

Around 900, autonomous stem duchies (Franconia, Bavaria, Swabia, Saxony, and Lotharingia) reemerged in East Francia. After the Carolingian king Louis the Child died without issue in 911, East Francia did not turn to the Carolingian ruler of West Francia to take over the realm but instead elected one of the dukes, Conrad of Franconia, as Rex Francorum Orientalium.[41]:117 On his deathbed, Conrad yielded the crown to his main rival, Henry the Fowler of Saxony (r. 919–36), who was elected king at the Diet of Fritzlar in 919.[41]:118 Henry reached a truce with the raiding Magyars, and in 933 he won a first victory against them in the Battle of Riade.[41]:121Henry died in 936, but his descendants, the Liudolfing (or Ottonian) dynasty, would continue to rule the Eastern kingdom for roughly a century. Upon Henry the Fowler's death, Otto, his son and designated successor,[42] was elected King in Aachen in 936.[43]:706 He overcame a series of revolts from a younger brother and from several dukes. After that, the king managed to control the appointment of dukes and often also employed bishops in administrative affairs.[44]:212–13

The Holy Roman Empire from 962 to 1806

The kingdom had no permanent capital city.[45] Kings traveled between residences (called Kaiserpfalz) to discharge affairs. However, each king preferred certain places; in Otto's case, this was the city of Magdeburg. Kingship continued to be transferred by election, but Kings often ensured their own sons were elected during their lifetimes, enabling them to keep the crown for their families. This only changed after the end of the Salian dynasty in the 12th century.

In 963, Otto deposed the current Pope John XII and chose Pope Leo VIII as the new pope (although John XII and Leo VIII both claimed the papacy until 964 when John XII died). This also renewed the conflict with the Eastern Emperor in Constantinople, especially after Otto's son Otto II (r. 967–83) adopted the designation imperator Romanorum. Still, Otto II formed marital ties with the east when he married the Byzantine princess Theophanu.[43]:708 Their son, Otto III, came to the throne only three years old, and was subjected to a power struggle and series of regencies until his age of majority in 994. Up to that time, he had remained in Germany, while a deposed Duke, Crescentius II, ruled over Rome and part of Italy, ostensibly in his stead.

In 996 Otto III appointed his cousin Gregory V the first German Pope.[46] A foreign pope and foreign papal officers were seen with suspicion by Roman nobles, who were led by Crescentius II to revolt. Otto III's former mentor Antipope John XVI briefly held Rome, until the Holy Roman Emperor seized the city.[47]

Otto died young in 1002, and was succeeded by his cousin Henry II, who focused on Germany.[44]:215–17

Henry II died in 1024 and Conrad II, first of the Salian Dynasty, was elected king only after some debate among dukes and nobles. This group eventually developed into the college of Electors.

The Holy Roman Empire became eventually composed of four kingdoms. The kingdoms were:

- Kingdom of Germany (part of the empire since 962),

- Kingdom of Italy (from 962 until 1648),

- Kingdom of Bohemia (since 1002 as the Duchy of Bohemia and raised to a kingdom in 1198),

- Kingdom of Burgundy (from 1032 to 1378).

High Middle Ages

Investiture controversy

Kings often employed bishops in administrative affairs and often determined who would be appointed to ecclesiastical offices.[48]:101–134 In the wake of the Cluniac Reforms, this involvement was increasingly seen as inappropriate by the Papacy. The reform-minded Pope Gregory VII was determined to oppose such practices, which led to the Investiture Controversy with King Henry IV (r. 1056–1106).[48]:101–134 He repudiated the Pope's interference and persuaded his bishops to excommunicate the Pope, whom he famously addressed by his born name "Hildebrand", rather than his regnal name "Pope Gregory VII".[48]:109 The Pope, in turn, excommunicated the king, declared him deposed, and dissolved the oaths of loyalty made to Henry.[11][48]:109 The king found himself with almost no political support and was forced to make the famous Walk to Canossa in 1077,[48]:122–24 by which he achieved a lifting of the excommunication at the price of humiliation. Meanwhile, the German princes had elected another king, Rudolf of Swabia.[48]:123 Henry managed to defeat him but was subsequently confronted with more uprisings, renewed excommunication, and even the rebellion of his sons. After his death, his second son, Henry V, reached an agreement with the Pope and the bishops in the 1122 Concordat of Worms.[48]:123–34 The political power of the Empire was maintained, but the conflict had demonstrated the limits of the ruler's power, especially in regard to the Church, and it robbed the king of the sacral status he had previously enjoyed. The Pope and the German princes had surfaced as major players in the political system of the empire.Holy Roman Empire under Hohenstaufen dynasty

The Hohenstaufen-ruled Holy Roman Empire and Kingdom of Sicily. Imperial and directly held Hohenstaufen lands in the Empire are shown in bright yellow.

The Hohenstaufen rulers increasingly lent land to ministerialia, formerly non-free servicemen, who Frederick hoped would be more reliable than dukes. Initially used mainly for war services, this new class of people would form the basis for the later knights, another basis of imperial power. A further important constitutional move at Roncaglia was the establishment of a new peace mechanism for the entire empire, the Landfrieden, with the first imperial one being issued in 1103 under Henry IV at Mainz.[49][50] This was an attempt to abolish private feuds, between the many dukes and other people, and to tie the Emperor's subordinates to a legal system of jurisdiction and public prosecution of criminal acts – a predecessor of the modern concept of "rule of law". Another new concept of the time was the systematic foundation of new cities by the Emperor and by the local dukes. These were partly caused by the explosion in population, and they also concentrated economic power at strategic locations. Before this, cities had only existed in the form of old Roman foundations or older bishoprics. Cities that were founded in the 12th century include Freiburg, possibly the economic model for many later cities, and Munich.

Frederick I, also called Frederick Barbarossa, was crowned Emperor in 1155. He emphasized the "Romanness" of the empire, partly in an attempt to justify the power of the Emperor independent of the (now strengthened) Pope. An imperial assembly at the fields of Roncaglia in 1158 reclaimed imperial rights in reference to Justinian's Corpus Juris Civilis. Imperial rights had been referred to as regalia since the Investiture Controversy but were enumerated for the first time at Roncaglia. This comprehensive list included public roads, tariffs, coining, collecting punitive fees, and the investiture or seating and unseating of office holders. These rights were now explicitly rooted in Roman Law, a far-reaching constitutional act.

Frederick's policies were primarily directed at Italy, where he clashed with the increasingly wealthy and free-minded cities of the north, especially Milan. He also embroiled himself in another conflict with the Papacy by supporting a candidate elected by a minority against Pope Alexander III (1159–81). Frederick supported a succession of antipopes before finally making peace with Alexander in 1177. In Germany, the Emperor had repeatedly protected Henry the Lion against complaints by rival princes or cities (especially in the cases of Munich and Lübeck). Henry gave only lackluster support to Frederick's policies, and in a critical situation during the Italian wars, Henry refused the Emperor's plea for military support. After returning to Germany, an embittered Frederick opened proceedings against the Duke, resulting in a public ban and the confiscation of all his territories. In 1190, Frederick participated in the Third Crusade and died in the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia.[51]

During the Hohenstaufen period, German princes facilitated a successful, peaceful eastward settlement of lands that were uninhabited or inhabited sparsely by West Slavs. German speaking farmers, traders, and craftsmen from the western part of the Empire, both Christians and Jews, moved into these areas. The gradual Germanization of these lands was a complex phenomenon that should not be interpreted in the biased terms of 19th-century nationalism. The eastward settlement expanded the influence of the empire to include Pomerania and Silesia, as did the intermarriage of the local, still mostly Slavic, rulers with German spouses. The Teutonic Knights were invited to Prussia by Duke Konrad of Masovia to Christianize the Prussians in 1226. The monastic state of the Teutonic Order (German: Deutschordensstaat) and its later German successor state of Prussia were, however, never part of the Holy Roman Empire.

Under the son and successor of Frederick Barbarossa, Henry VI, the Hohenstaufen dynasty reached its apex. Henry added the Norman kingdom of Sicily to his domains, held English king Richard the Lionheart captive, and aimed to establish a hereditary monarchy when he died in 1197. As his son, Frederick II, though already elected king, was still a small child and living in Sicily, German princes chose to elect an adult king, resulting in the dual election of Frederick Barbarossa's youngest son Philip of Swabia and Henry the Lion's son Otto of Brunswick, who competed for the crown. Otto prevailed for a while after Philip was murdered in a private squabble in 1208 until he began to also claim Sicily.

The Reichssturmfahne, a military banner during the 13th and early 14th centuries.

Despite his imperial claims, Frederick's rule was a major turning point towards the disintegration of central rule in the Empire. While concentrated on establishing a modern, centralized state in Sicily, he was mostly absent from Germany and issued far-reaching privileges to Germany's secular and ecclesiastical princes: In the 1220 Confoederatio cum principibus ecclesiasticis, Frederick gave up a number of regalia in favour of the bishops, among them tariffs, coining, and fortification. The 1232 Statutum in favorem principum mostly extended these privileges to secular territories. Although many of these privileges had existed earlier, they were now granted globally, and once and for all, to allow the German princes to maintain order north of the Alps while Frederick concentrated on Italy. The 1232 document marked the first time that the German dukes were called domini terræ, owners of their lands, a remarkable change in terminology as well.

Kingdom of Bohemia

Lands of the Bohemian Crown since the reign of Holy Roman Emperor Charles IV

Interregnum

After the death of Frederick II in 1250, the German kingdom was divided between his son Conrad IV (died 1254) and the anti-king, William of Holland (died 1256). Conrad's death was followed by the Interregnum, during which no king could achieve universal recognition, allowing the princes to consolidate their holdings and become even more independent rulers. After 1257, the crown was contested between Richard of Cornwall, who was supported by the Guelph party, and Alfonso X of Castile, who was recognized by the Hohenstaufen party but never set foot on German soil. After Richard's death in 1273, the Interregnum ended with the unanimous election of Rudolf I of Germany, a minor pro-Staufen count.Changes in political structure

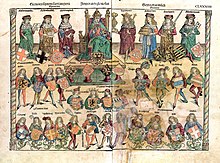

An illustration from Schedelsche Weltchronik

depicting the structure of the Reich: The Holy Roman Emperor is

sitting; on his right are three ecclesiastics; on his left are four

secular electors.

During this time territories began to transform into the predecessors of modern states. The process varied greatly among the various lands and was most advanced in those territories that were almost identical to the lands of the old Germanic tribes, e.g. Bavaria. It was slower in those scattered territories that were founded through imperial privileges.

Late Middle Ages

Rise of the territories after the Hohenstaufens

Double-headed eagle with coats of arms of individual states, the symbol of the Holy Roman Empire (painting from 1510)

The shift in power away from the emperor is also revealed in the way the post-Hohenstaufen kings attempted to sustain their power. Earlier, the Empire's strength (and finances) greatly relied on the Empire's own lands, the so-called Reichsgut, which always belonged to the king of the day and included many Imperial Cities. After the 13th century, the relevance of the Reichsgut faded, even though some parts of it did remain until the Empire's end in 1806. Instead, the Reichsgut was increasingly pawned to local dukes, sometimes to raise money for the Empire, but more frequently to reward faithful duty or as an attempt to establish control over the dukes. The direct governance of the Reichsgut no longer matched the needs of either the king or the dukes.

The kings beginning with Rudolf I of Germany increasingly relied on the lands of their respective dynasties to support their power. In contrast with the Reichsgut, which was mostly scattered and difficult to administer, these territories were relatively compact and thus easier to control. In 1282, Rudolf I thus lent Austria and Styria to his own sons. In 1312, Henry VII of the House of Luxembourg was crowned as the first Holy Roman Emperor since Frederick II. After him all kings and emperors relied on the lands of their own family (Hausmacht): Louis IV of Wittelsbach (king 1314, emperor 1328–47) relied on his lands in Bavaria; Charles IV of Luxembourg, the grandson of Henry VII, drew strength from his own lands in Bohemia. Interestingly, it was thus increasingly in the king's own interest to strengthen the power of the territories, since the king profited from such a benefit in his own lands as well.

Imperial reform

The Holy Roman Empire in 1400

Simultaneously, the Catholic Church experienced crises of its own, with wide-reaching effects in the Empire. The conflict between several papal claimants (two anti-popes and the "legitimate" Pope) ended only with the Council of Constance (1414–1418); after 1419 the Papacy directed much of its energy to suppress the Hussites. The medieval idea of unifying all Christendom into a single political entity, with the Church and the Empire as its leading institutions, began to decline.

With these drastic changes, much discussion emerged in the 15th century about the Empire itself. Rules from the past no longer adequately described the structure of the time, and a reinforcement of earlier Landfrieden was urgently needed. During this time, the concept of "reform" emerged, in the original sense of the Latin verb re-formare – to regain an earlier shape that had been lost.

When Frederick III needed the dukes to finance a war against Hungary in 1486, and at the same time had his son (later Maximilian I) elected king, he faced a demand from the united dukes for their participation in an Imperial Court. For the first time, the assembly of the electors and other dukes was now called the Imperial Diet (German Reichstag) (to be joined by the Imperial Free Cities later). While Frederick refused, his more conciliatory son finally convened the Diet at Worms in 1495, after his father's death in 1493. Here, the king and the dukes agreed on four bills, commonly referred to as the Reichsreform (Imperial Reform): a set of legal acts to give the disintegrating Empire some structure. For example, this act produced the Imperial Circle Estates and the Reichskammergericht (Imperial Chamber Court), institutions that would – to a degree – persist until the end of the Empire in 1806.

However, it took a few more decades for the new regulation to gain universal acceptance and for the new court to begin to function effectively; only in 1512 would the Imperial Circles be finalized. The King also made sure that his own court, the Reichshofrat, continued to operate in parallel to the Reichskammergericht. Also in 1512, the Empire received its new title, the Heiliges Römisches Reich Deutscher Nation ("Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation").

Reformation and Renaissance

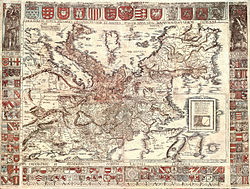

Carta itineraria europae (by Waldseemüller, 1520 dedicated to Emperor Charles V.)

In addition to conflicts between his Spanish and German inheritances, conflicts of religion would be another source of tension during the reign of Charles V. Before Charles's reign in the Holy Roman Empire began, in 1517, Martin Luther launched what would later be known as the Reformation. At this time, many local dukes saw it as a chance to oppose the hegemony of Emperor Charles V. The empire then became fatally divided along religious lines, with the north, the east, and many of the major cities – Strasbourg, Frankfurt, and Nuremberg – becoming Protestant while the southern and western regions largely remained Catholic.

Baroque period

Religion in the Holy Roman Empire on the eve of the Thirty Years' War

The Holy Roman Empire around 1600, superimposed over current state borders

The Empire after the Peace of Westphalia, 1648

Germany would enjoy relative peace for the next six decades. On the eastern front, the Turks continued to loom large as a threat, although war would mean further compromises with the Protestant princes, and so the Emperor sought to avoid it. In the west, the Rhineland increasingly fell under French influence. After the Dutch revolt against Spain erupted, the Empire remained neutral, de facto allowing the Netherlands to depart the empire in 1581, a secession acknowledged in 1648. A side effect was the Cologne War, which ravaged much of the upper Rhine.

After Ferdinand died in 1564, his son Maximilian II became Emperor, and like his father accepted the existence of Protestantism and the need for occasional compromise with it. Maximilian was succeeded in 1576 by Rudolf II, a strange man who preferred classical Greek philosophy to Christianity and lived an isolated existence in Bohemia. He became afraid to act when the Catholic Church was forcibly reasserting control in Austria and Hungary, and the Protestant princes became upset over this. Imperial power sharply deteriorated by the time of Rudolf's death in 1612. When Bohemians rebelled against the Emperor, the immediate result was the series of conflicts known as the Thirty Years' War (1618–48), which devastated the Empire. Foreign powers, including France and Sweden, intervened in the conflict and strengthened those fighting Imperial power, but also seized considerable territory for themselves. The long conflict so bled the Empire that it never recovered its strength.

The actual end of the empire came in several steps. The Peace of Westphalia in 1648, which ended the Thirty Years' War, gave the territories almost complete independence. Calvinism was now allowed, but Anabaptists, Arminians and other Protestant communities would still lack any support and continue to be persecuted well until the end of the Empire. The Swiss Confederation, which had already established quasi-independence in 1499, as well as the Northern Netherlands, left the Empire. The Habsburg Emperors focused on consolidating their own estates in Austria and elsewhere.

At the Battle of Vienna (1683), the Army of the Holy Roman Empire, led by the Polish King John III Sobieski, decisively defeated a large Turkish army, stopping the western Ottoman advance and leading to the eventual dismemberment of the Ottoman Empire in Europe. The army was half forces of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, mostly cavalry, and half forces of the Holy Roman Empire (German/Austrian), mostly infantry.

Modern period

Prussia and Austria

By the rise of Louis XIV, the Habsburgs were chiefly dependent on their hereditary lands to counter the rise of Prussia; some of whose territories lay inside the Empire. Throughout the 18th century, the Habsburgs were embroiled in various European conflicts, such as the War of the Spanish Succession, the War of the Polish Succession, and the War of the Austrian Succession. The German dualism between Austria and Prussia dominated the empire's history after 1740.French Revolutionary Wars and final dissolution

The Empire on the eve of the French Revolution, 1789

The German mediatization was the series of mediatizations and secularizations that occurred between 1795 and 1814, during the latter part of the era of the French Revolution and then the Napoleonic Era. "Mediatization" was the process of annexing the lands of one imperial estate to another, often leaving the annexed some rights. For example, the estates of the Imperial Knights were formally mediatized in 1806, having de facto been seized by the great territorial states in 1803 in the so-called Rittersturm. "Secularization" was the abolition of the temporal power of an ecclesiastical ruler such as a bishop or an abbot and the annexation of the secularized territory to a secular territory.

The empire was dissolved on 6 August 1806, when the last Holy Roman Emperor Francis II (from 1804, Emperor Francis I of Austria) abdicated, following a military defeat by the French under Napoleon at Austerlitz (see Treaty of Pressburg). Napoleon reorganized much of the Empire into the Confederation of the Rhine, a French satellite. Francis' House of Habsburg-Lorraine survived the demise of the empire, continuing to reign as Emperors of Austria and Kings of Hungary until the Habsburg empire's final dissolution in 1918 in the aftermath of World War I.

The Napoleonic Confederation of the Rhine was replaced by a new union, the German Confederation, in 1815, following the end of the Napoleonic Wars. It lasted until 1866 when Prussia founded the North German Confederation, a forerunner of the German Empire which united the German-speaking territories outside of Austria and Switzerland under Prussian leadership in 1871. This state developed into modern Germany.

The only princely member state of the Holy Roman Empire that has preserved its status as a monarchy until today is the Principality of Liechtenstein. The only Free Imperial Cities still being states within Germany are Hamburg and Bremen. All other historic member states of the HRE were either dissolved or are republican successor states to their princely predecessor states.

Institutions

The Holy Roman Empire was not a highly centralized state like most countries today. Instead, it was divided into dozens – eventually hundreds – of individual entities governed by kings,[54] dukes, counts, bishops, abbots, and other rulers, collectively known as princes. There were also some areas ruled directly by the Emperor. At no time could the Emperor simply issue decrees and govern autonomously over the Empire. His power was severely restricted by the various local leaders.From the High Middle Ages onwards, the Holy Roman Empire was marked by an uneasy coexistence of the princes of the local territories who were struggling to take power away from it. To a greater extent than in other medieval kingdoms such as France and England, the Emperors were unable to gain much control over the lands that they formally owned. Instead, to secure their own position from the threat of being deposed, Emperors were forced to grant more and more autonomy to local rulers, both nobles, and bishops. This process began in the 11th century with the Investiture Controversy and was more or less concluded with the 1648 Peace of Westphalia. Several Emperors attempted to reverse this steady dissemination of their authority but were thwarted both by the papacy and by the princes of the Empire.

Imperial estates

The number of territories represented in the Imperial Diet was considerable, numbering about 300 at the time of the Peace of Westphalia. Many of these Kleinstaaten ("little states") covered no more than a few square miles, and/or included several non-contiguous pieces, so the Empire was often called a Flickenteppich ("patchwork carpet"). An entity was considered a Reichsstand (imperial estate) if, according to feudal law, it had no authority above it except the Holy Roman Emperor himself. The imperial estates comprised:- Territories ruled by a hereditary nobleman, such as a prince, archduke, duke, or count.

- Territories in which secular authority was held by a clerical dignitary, such as an archbishop, bishop, or abbot. Such a cleric was a prince of the church. In the common case of a prince-bishop, this temporal territory (called a prince-bishopric) frequently overlapped with his often-larger ecclesiastical diocese, giving the bishop both civil and clerical powers. Examples are the prince-archbishoprics of Cologne, Trier, and Mainz.

- Free imperial cities and Imperial villages, which were subject only to the jurisdiction of the emperor.

- The scattered estates of the free Imperial Knights and Imperial Counts, immediate to the Emperor but unrepresented in the Imperial Diet.

King of the Romans

The crown of the Holy Roman Empire (2nd half of the 10th century), now held in the Schatzkammer (Vienna)

After being elected, the King of the Romans could theoretically claim the title of "Emperor" only after being crowned by the Pope. In many cases, this took several years while the King was held up by other tasks: frequently he first had to resolve conflicts in rebellious northern Italy or was quarreling with the Pope himself. Later Emperors dispensed with the papal coronation altogether, being content with the styling Emperor-Elect: the last Emperor to be crowned by the Pope was Charles V in 1530.

The Emperor had to be male and of noble blood. No law required him to be a Catholic, but as the majority of the Electors adhered to this faith, no Protestant was ever elected. Whether and to what degree he had to be German was disputed among the Electors, contemporary experts in constitutional law, and the public. During the Middle Ages, some Kings and Emperors were not of German origin, but since the Renaissance, German heritage was regarded as vital for a candidate in order to be eligible for imperial office.[56]

Imperial Diet (Reichstag)

The Seven Prince-electors

The third class was the Council of Imperial Cities, which was divided into two colleges: Swabia and the Rhine. The Council of Imperial Cities was not fully equal with the others; it could not vote on several matters such as the admission of new territories. The representation of the Free Cities at the Diet had become common since the late Middle Ages. Nevertheless, their participation was formally acknowledged only as late as in 1648 with the Peace of Westphalia ending the Thirty Years' War.

Imperial courts

The Empire also had two courts: the Reichshofrat (also known in English as the Aulic Council) at the court of the King/Emperor, and the Reichskammergericht (Imperial Chamber Court), established with the Imperial Reform of 1495.Imperial circles

Map of the Empire showing division into Circles in 1512

Army

The Army of the Holy Roman Empire (German Reichsarmee, Reichsheer or Reichsarmatur; Latin exercitus imperii) was created in 1422 and came to an end even before the Empire as the result of the Napoleonic Wars. It must not be confused with the Imperial Army (Kaiserliche Armee) of the Emperor.Despite appearances to the contrary, the Army of the Empire did not constitute a permanent standing army that was always at the ready to fight for the Empire. When there was danger, an Army of the Empire was mustered from among the elements constituting it,[58] in order to conduct an imperial military campaign or Reichsheerfahrt. In practice, the imperial troops often had local allegiances stronger than their loyalty to the Emperor.

Administrative centres

Reichshofrat resided in Vienna.Reichskammergericht resided in Worms, Augsburg, Nuremberg, Regensburg, Speyer and Esslingen before it was moved permanently to Wetzlar.

Reichstag resided variously in Paderborn, Bad Lippspringe, Ingelheim am Rhein, Diedenhofen (now Thionville), Aachen, Worms, Forchheim, Trebur, Fritzlar, Ravenna, Quedlinburg, Dortmund, Verona, Minden, Mainz, Frankfurt am Main, Merseburg, Goslar, Würzburg, Bamberg, Schwäbisch Hall, Augsburg, Nuremberg, Quierzy-sur-Oise, Speyer, Gelnhausen, Erfurt, Eger (now Cheb), Esslingen, Lindau, Freiburg, Cologne, Konstanz and Trier before it was moved permanently to Regensburg.

The Holy Roman Empire never had a capital city. Usually, the Holy Roman Emperor ruled from a place of his own choice. This was called an imperial seat. Seats of the Holy Roman Emperor included: Aachen (from 794), Munich (1328–1347 and 1744–1745), Prague (1355–1437 and 1576–1611), Vienna (1438–1576, 1611–1740 and 1745–1806) and Frankfurt am Main (1742–1744) among other cities.

Imperial elections were mostly held in Frankfurt am Main, but also took place in Augsburg, Rhens, Cologne and Regensburg. Going as far as into the 16th century, the elected Holy Roman Emperor was then crowned and appointed by the Pope in Rome, but individual coronations also happened in Ravenna, Bologna and Reims.

Demographics

Population

| Year | Population | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| 1500 | 16,000,000 | [2][3] |

| 1618 | 21,000,000 | [4] |

| 1648 | 16,000,000 | [4] |

| 1786 | 26,265,000 | [5] |

| 1800 | 24,000,000 | [59] |

Largest cities

Largest cities or towns of the Empire by year:- 1050: Regensburg 40,000 people. Rome 35,000. Mainz 30,000. Speyer 25,000. Cologne 21,000. Trier 20,000. Worms 20,000. Lyon 20,000. Verona 20,000. Florence 15,000.[60]

- 1300–1350: Prague 77,000 people. Cologne 54,000 people. Aachen 21,000 people. Magdeburg 20,000 people. Nuremberg 20,000 people. Vienna 20,000 people. Danzig (now Gdańsk) 20,000 people. Straßburg (now Strasbourg) 20,000 people. Lübeck 15,000 people. Regensburg 11,000 people.[61][62][63][64]

- 1500: Prague 70,000. Cologne 45,000. Nuremberg 38,000. Augsburg 30,000. Danzig (now Gdańsk) 30,000. Lübeck 25,000. Breslau (now Wrocław) 25,000. Regensburg 22,000. Vienna 20,000. Straßburg (now Strasbourg) 20,000. Magdeburg 18,000. Ulm 16,000. Hamburg 15,000.[65]

- 1600: Prague 100,000. Vienna 50,000. Augsburg 45,000. Cologne 40,000. Nuremberg 40,000. Hamburg 40,000. Magdeburg 40,000. Breslau (now Wrocław) 40,000. Straßburg (now Strasbourg) 25,000. Lübeck 23,000. Ulm 21,000. Regensburg 20,000. Frankfurt am Main 20,000. Munich 20,000.[65]

Religion

Front page of the Peace of Augsburg, which laid the legal groundwork for two co-existing religious confessions (Roman Catholicism and Lutheranism) in the German-speaking states of the Holy Roman Empire.

Lutheranism was officially recognized in the Peace of Augsburg of 1555, and Calvinism in the Peace of Westphalia of 1648. Those two constituted the only officially recognized Protestant denominations, while various other Protestant confessions such as Anabaptism, Arminianism, etc. coexisted illegally within the Empire. Anabaptism came in a variety of denominations, including Mennonites, Schwarzenau Brethren, Hutterites, the Amish, and multiple other groups.

Comments

Post a Comment