Maurya Empire

Maurya Empire

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

| Maurya Empire | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

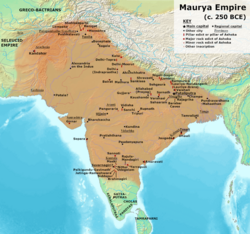

The maximum extent of the Maurya Empire, as shown in many modern maps.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Pataliputra (Present-day Patna, Bihar) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Languages | Sanskrit, Magadhi Prakrit | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Buddhism Jainism Ājīvika | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Absolute monarchy, as described in Chanakya's Arthashastra | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Emperor | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • | 322–298 BCE | Chandragupta | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| • | 298–272 BCE | Bindusara | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| • | 268–232 BCE | Ashoka | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| • | 232–224 BCE | Dasharatha | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| • | 224–215 BCE | Samprati | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| • | 215–202 BCE | Shalishuka | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| • | 202–195 BCE | Devavarman | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| • | 195–187 BCE | Shatadhanvan | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| • | 187–180 BCE | Brihadratha | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Antiquity | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| • | Established | 322 BCE | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| • | Disestablished | 180 BCE | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Area | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • | 250 BCE[1] | 5,000,000 km2 (1,900,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Panas | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | India Pakistan Bangladesh Afghanistan Nepal Iran | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Maurya Empire (322 BCE–180 BCE) | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

Chandragupta Maurya raised an army, with the assistance of Chanakya (also known as Kauṭilya),[4] and overthrew the Nanda Empire in c. 322 BCE. Chandragupta rapidly expanded his power westwards across central and western India by conquering the satraps left by Alexander the Great, and by 317 BCE the empire had fully occupied Northwestern India.[5] The Mauryan Empire then defeated Seleucus I, a diadochus and founder of the Seleucid Empire, during the Seleucid–Mauryan war, thus gained additional territory west of the Indus River.[6]

The Maurya Empire was one of the largest empires of the world. At its greatest extent, the empire stretched to the north along the natural boundaries of the Himalayas, to the east into Assam, to the west into Balochistan (southwest Pakistan and southeast Iran) and the Hindu Kush mountains of what is now Afghanistan.[7] The Empire was expanded into India's central and southern regions[8][9] by the emperors Chandragupta and Bindusara, but it excluded Kalinga (modern Odisha), until it was conquered by Ashoka.[10] It declined for about 50 years after Ashoka's rule ended, and it dissolved in 185 BCE with the foundation of the Shunga dynasty in Magadha.

Under Chandragupta Maurya and his successors, internal and external trade, agriculture, and economic activities all thrived and expanded across India thanks to the creation of a single and efficient system of finance, administration, and security. After the Kalinga War, the Empire experienced nearly half a century of peace and security under Ashoka. Mauryan India also enjoyed an era of social harmony, religious transformation, and expansion of the sciences and of knowledge. Chandragupta Maurya's embrace of Jainism increased social and religious renewal and reform across his society, while Ashoka's embrace of Buddhism has been said to have been the foundation of the reign of social and political peace and non-violence across all of India. Ashoka sponsored the spreading of Buddhist missionaries into Sri Lanka, Southeast Asia, West Asia, North Africa, and Mediterranean Europe.[11]

The population of the empire has been estimated to be about 50–60 million, making the Mauryan Empire one of the most populous empires of Antiquity.[12][13] Archaeologically, the period of Mauryan rule in South Asia falls into the era of Northern Black Polished Ware (NBPW). The Arthashastra[14] and the Edicts of Ashoka are the primary sources of written records of Mauryan times. The Lion Capital of Ashoka at Sarnath has been made the national emblem of India.

Contents

History

Chandragupta Maurya and Chanakya

The Maurya Empire was founded by Chandragupta Maurya, with help from Chanakya, at Takshashila, a noted center of learning. According to several legends, Chanakya travelled to Magadha, a kingdom that was large and militarily powerful and feared by its neighbours, but was insulted by its king Dhana Nanda, of the Nanda dynasty. Chanakya swore revenge and vowed to destroy the Nanda Empire.[15] Meanwhile, the conquering armies of Alexander the Great refused to cross the Beas River and advance further eastward, deterred by the prospect of battling Magadha. Alexander returned to Babylon and re-deployed most of his troops west of the Indus River. Soon after Alexander died in Babylon in 323 BCE, his empire fragmented into independent kingdoms led by his generals.[16]The Greek generals Eudemus and Peithon ruled in the Indus Valley until around 317 BCE, when Chandragupta Maurya (with the help of Chanakya, who was now his advisor) orchestrated a rebellion to drive out the Greek governors, and subsequently brought the Indus Valley under the control of his new seat of power in Magadha.[5]

Chandragupta Maurya's rise to power is shrouded in mystery and controversy. On one hand, a number of ancient Indian accounts, such as the drama Mudrarakshasa (Signet ring of Rakshasa – Rakshasa was the prime minister of Magadha) by Vishakhadatta, describe his royal ancestry and even link him with the Nanda family. A kshatriya clan known as the Maurya's are referred to in the earliest Buddhist texts, Mahaparinibbana Sutta. However, any conclusions are hard to make without further historical evidence. Chandragupta first emerges in Greek accounts as "Sandrokottos". As a young man he is said to have met Alexander.[17] He is also said to have met the Nanda king, angered him, and made a narrow escape.[18] Chanakya's original intentions were to train a guerilla army under Chandragupta's command.

Conquest of Magadha

| Territorial evolution of the Mauryan Empire | |

| |

- "Kusumapura was besieged from every direction by the forces of Parvata and Chandragupta: Shakas, Yavanas, Kiratas, Kambojas, Parasikas, Bahlikas and others, assembled on the advice of Chanakya" in Mudrarakshasa 2 [26][24]

Chandragupta Maurya

Pataliputra, capital of the Mauryas. Ruins of pillared hall at Kumrahar site.

The Pataliputra capital, discovered at the Bulandi Bagh site of Pataliputra, 4th-3rd c. BCE.

Chandragupta established a strong centralized state with an administration at Pataliputra, which, according to Megasthenes, was "surrounded by a wooden wall pierced by 64 gates and 570 towers". Aelian, although not expressly quoting Megasthenes nor mentionning Pataliputra, described Indian palaces as superior in splendor to Persia's Susa or Ectabana.[29] The architecture of the city seems to have had many similarities with Persian cities of the period.[30]

Chandragupta's son Bindusara extended the rule of the Mauryan empire towards southern India. The famous Tamil poet Mamulanar of the Sangam literature described how the Deccan Plateau was invaded by the Maurya army.[31] He also had a Greek ambassador at his court, named Megasthenes.[32]

Megasthenes describes a disciplined multitude under Chandragupta, who live simply, honestly, and do not know writing:

- "The Indians all live frugally, especially when in camp. They dislike a great undisciplined multitude, and consequently they observe good order. Theft is of very rare occurrence. Megasthenes says that those who were in the camp of Sandrakottos, wherein lay 400,000 men, found that the thefts reported on any one day did not exceed the value of two hundred drachmae, and this among a people who have no written laws, but are ignorant of writing, and must therefore in all the business of life trust to memory. They live, nevertheless, happily enough, being simple in their manners and frugal. They never drink wine except at sacrifices. Their beverage is a liquor composed from rice instead of barley, and their food is principally a rice-pottage." Strabo XV. i. 53–56, quoting Megasthenes.

Bindusara

A silver coin of 1 karshapana of the Maurya empire, period of Bindusara Maurya about 297-272 BC, workshop of Pataliputra. Obv: Symbols with a Sun Rev: Symbol Dimensions: 14 x 11 mm Weight: 3.4 g.

Bindusara extended the borders of the empire southward into the Deccan Plateau c. 300 BCE.[37]

Historian Upinder Singh estimates that Bindusara ascended the throne around 297 BCE.[44] Bindusara, just 22 years old, inherited a large empire that consisted of what is now, Northern, Central and Eastern parts of India along with parts of Afghanistan and Baluchistan. Bindusara extended this empire to the southern part of India, as far as what is now known as Karnataka. He brought sixteen states under the Mauryan Empire and thus conquered almost all of the Indian peninsula (he is said to have conquered the 'land between the two seas' – the peninsular region between the Bay of Bengal and the Arabian Sea). Bindusara didn't conquer the friendly Tamil kingdoms of the Cholas, ruled by King Ilamcetcenni, the Pandyas, and Cheras. Apart from these southern states, Kalinga (modern Odisha) was the only kingdom in India that didn't form the part of Bindusara's empire.[45] It was later conquered by his son Ashoka, who served as the viceroy of Ujjaini during his father's reign, which highlights the importance of the town.[46][47]

Bindusara's life has not been documented as well as that of his father Chandragupta or of his son Ashoka. Chanakya continued to serve as prime minister during his reign. According to the medieval Tibetan scholar Taranatha who visited India, Chanakya helped Bindusara "to destroy the nobles and kings of the sixteen kingdoms and thus to become absolute master of the territory between the eastern and western oceans."[48] During his rule, the citizens of Taxila revolted twice. The reason for the first revolt was the maladministration of Susima, his eldest son. The reason for the second revolt is unknown, but Bindusara could not suppress it in his lifetime. It was crushed by Ashoka after Bindusara's death.[49]

Bindusara maintained friendly diplomatic relations with the Hellenic World. Deimachus was the ambassador of Seleucid emperor Antiochus I at Bindusara's court.[50] Diodorus states that the king of Palibothra (Pataliputra, the Mauryan capital) welcomed a Greek author, Iambulus. This king is usually identified as Bindusara.[50] Pliny states that the Egyptian king Philadelphus sent an envoy named Dionysius to India.[51][52] According to Sailendra Nath Sen, this appears to have happened during Bindusara's reign.[50]

Unlike his father Chandragupta (who at a later stage converted to Jainism), Bindusara believed in the Ajivika sect. Bindusara's guru Pingalavatsa (Janasana) was a Brahmin[53] of the Ajivika sect. Bindusara's wife, Queen Subhadrangi (Queen Aggamahesi) was a Brahmin[54] also of the Ajivika sect from Champa (present Bhagalpur district). Bindusara is credited with giving several grants to Brahmin monasteries (Brahmana-bhatto).[55]

Historical evidence suggests that Bindusara died in the 270s BCE. According to Upinder Singh, Bindusara died around 273 BCE.[44] Alain Daniélou believes that he died around 274 BCE.[56] Sailendra Nath Sen believes that he died around 273-272 BCE, and that his death was followed by a four-year struggle of succession, after which his son Ashoka became the emperor in 269-268 BCE.[50] According to the Mahavamsa, Bindusara reigned for 28 years.[57] The Vayu Purana, which names Chandragupta's successor as "Bhadrasara", states that he ruled for 25 years.[58]

Ashoka

Aśoka pillar at Sarnath. ca. 250 BCE.

Ashoka pillar at Vaishali.

Ashoka implemented principles of ahimsa by banning hunting and violent sports activity and ending indentured and forced labor (many thousands of people in war-ravaged Kalinga had been forced into hard labour and servitude). While he maintained a large and powerful army, to keep the peace and maintain authority, Ashoka expanded friendly relations with states across Asia and Europe, and he sponsored Buddhist missions. He undertook a massive public works building campaign across the country. Over 40 years of peace, harmony and prosperity made Ashoka one of the most successful and famous monarchs in Indian history. He remains an idealized figure of inspiration in modern India.[citation needed]

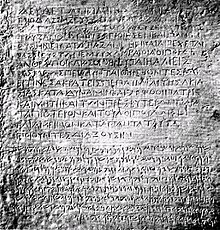

The Edicts of Ashoka, set in stone, are found throughout the Subcontinent. Ranging from as far west as Afghanistan and as far south as Andhra (Nellore District), Ashoka's edicts state his policies and accomplishments. Although predominantly written in Prakrit, two of them were written in Greek, and one in both Greek and Aramaic. Ashoka's edicts refer to the Greeks, Kambojas, and Gandharas as peoples forming a frontier region of his empire. They also attest to Ashoka's having sent envoys to the Greek rulers in the West as far as the Mediterranean. The edicts precisely name each of the rulers of the Hellenic world at the time such as Amtiyoko (Antiochus), Tulamaya (Ptolemy), Amtikini (Antigonos), Maka (Magas) and Alikasudaro (Alexander) as recipients of Ashoka's proselytism.[citation needed] The Edicts also accurately locate their territory "600 yojanas away" (a yojanas being about 7 miles), corresponding to the distance between the center of India and Greece (roughly 4,000 miles).[60]

Decline

Ashoka was followed for 50 years by a succession of weaker kings. Brihadratha, the last ruler of the Mauryan dynasty, held territories that had shrunk considerably from the time of emperor Ashoka. Brihadratha was assassinated in 185 BCE during a military parade by the Brahmin general Pushyamitra Shunga, commander-in-chief of his guard, who then took over the throne and established the Shunga dynasty.[61]Shunga coup (185 BCE)

Buddhist records such as the Ashokavadana write that the assassination of Brihadratha and the rise of the Shunga empire led to a wave of religious persecution for Buddhists,[62] and a resurgence of Hinduism. According to Sir John Marshall,[63] Pushyamitra may have been the main author of the persecutions, although later Shunga kings seem to have been more supportive of Buddhism. Other historians, such as Etienne Lamotte[64] and Romila Thapar,[65] among others, have argued that archaeological evidence in favour of the allegations of persecution of Buddhists are lacking, and that the extent and magnitude of the atrocities have been exaggerated.Establishment of the Indo-Greek Kingdom (180 BCE)

The fall of the Mauryas left the Khyber Pass unguarded, and a wave of foreign invasion followed. The Greco-Bactrian king, Demetrius, capitalized on the break-up, and he conquered southern Afghanistan and parts of northwestern India around 180 BCE, forming the Indo-Greek Kingdom. The Indo-Greeks would maintain holdings on the trans-Indus region, and make forays into central India, for about a century. Under them, Buddhism flourished, and one of their kings, Menander, became a famous figure of Buddhism; he was to establish a new capital of Sagala, the modern city of Sialkot. However, the extent of their domains and the lengths of their rule are subject to much debate. Numismatic evidence indicates that they retained holdings in the subcontinent right up to the birth of Christ. Although the extent of their successes against indigenous powers such as the Shungas, Satavahanas, and Kalingas are unclear, what is clear is that Scythian tribes, renamed Indo-Scythians, brought about the demise of the Indo-Greeks from around 70 BCE and retained lands in the trans-Indus, the region of Mathura, and Gujarat.[citation needed]Administration

Statuettes of the Mauryan era

Historians theorise that the organisation of the Empire was in line with the extensive bureaucracy described by Kautilya in the Arthashastra: a sophisticated civil service governed everything from municipal hygiene to international trade. The expansion and defense of the empire was made possible by what appears to have been one of the largest armies in the world during the Iron Age.[66] According to Megasthenes, the empire wielded a military of 600,000 infantry, 30,000 cavalry, 8,000 chariots and 9,000 war elephants besides followers and attendants.[67] A vast espionage system collected intelligence for both internal and external security purposes. Having renounced offensive warfare and expansionism, Ashoka nevertheless continued to maintain this large army, to protect the Empire and instil stability and peace across West and South Asia.[citation needed]

Economy

Maurya statuette, 2nd century BCE.

Under the Indo-Greek friendship treaty, and during Ashoka's reign, an international network of trade expanded. The Khyber Pass, on the modern boundary of Pakistan and Afghanistan, became a strategically important port of trade and intercourse with the outside world. Greek states and Hellenic kingdoms in West Asia became important trade partners of India. Trade also extended through the Malay peninsula into Southeast Asia. India's exports included silk goods and textiles, spices and exotic foods. The external world came across new scientific knowledge and technology with expanding trade with the Mauryan Empire. Ashoka also sponsored the construction of thousands of roads, waterways, canals, hospitals, rest-houses and other public works. The easing of many over-rigorous administrative practices, including those regarding taxation and crop collection, helped increase productivity and economic activity across the Empire.[citation needed]

In many ways, the economic situation in the Mauryan Empire is analogous to the Roman Empire of several centuries later. Both had extensive trade connections and both had organizations similar to corporations. While Rome had organizational entities which were largely used for public state-driven projects, Mauryan India had numerous private commercial entities. These existed purely for private commerce and developed before the Mauryan Empire itself.[68][unreliable source?]

| Maurya Empire coinage |

|

Religion

Jainism

Bhadrabahu Cave, Shravanabelagola where Chandragupta is said to have died

Thus, Jainism became a vital force under the Mauryan Rule. Chandragupta and Samprati are credited for the spread of Jainism in South India. Hundreds of thousands of temples and stupas are said to have been erected during their reigns.

Buddhism

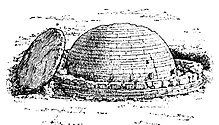

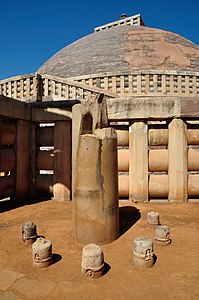

The stupa, which contained the relics of Buddha, at the center of the Sanchi complex was originally built by the Maurya Empire, but the balustrade around it is Sunga, and the decorative gateways are from the later Satavahana period.

The Dharmarajika stupa in Taxila, modern Pakistan, is also thought to have been established by Emperor Asoka.

Architectural remains

Mauryan architecture in the Barabar Caves. Lomas Rishi Cave. 3rd century BCE.

The peacock was a dynastic symbol of Mauryans, as depicted by Ashoka's pillars at Nandangarh and Sanchi Stupa.[77]

| Maurya structures and decorations at Sanchi (3rd century BCE) | |

Approximate reconstitution of the Great Stupa at Sanchi under the Mauryas. |

|

Natural history

The two Yakshas, possibly 3rd century BCE, found in Pataliputra.

The Mauryas firstly looked at forests as resources. For them, the most important forest product was the elephant. Military might in those times depended not only upon horses and men but also battle-elephants; these played a role in the defeat of Seleucus, one of Alexander's former generals. The Mauryas sought to preserve supplies of elephants since it was cheaper and took less time to catch, tame and train wild elephants than to raise them. Kautilya's Arthashastra contains not only maxims on ancient statecraft, but also unambiguously specifies the responsibilities of officials such as the Protector of the Elephant Forests.[80]

On the border of the forest, he should establish a forest for elephants guarded by foresters. The Office of the Chief Elephant Forester should with the help of guards protect the elephants in any terrain. The slaying of an elephant is punishable by death.The Mauryas also designated separate forests to protect supplies of timber, as well as lions and tigers for skins. Elsewhere the Protector of Animals also worked to eliminate thieves, tigers and other predators to render the woods safe for grazing cattle.[citation needed]

The Mauryas valued certain forest tracts in strategic or economic terms and instituted curbs and control measures over them. They regarded all forest tribes with distrust and controlled them with bribery and political subjugation. They employed some of them, the food-gatherers or aranyaca to guard borders and trap animals. The sometimes tense and conflict-ridden relationship nevertheless enabled the Mauryas to guard their vast empire.[81]

When Ashoka embraced Buddhism in the latter part of his reign, he brought about significant changes in his style of governance, which included providing protection to fauna, and even relinquished the royal hunt. He was the first ruler in history[not in citation given] to advocate conservation measures for wildlife and even had rules inscribed in stone edicts. The edicts proclaim that many followed the king's example in giving up the slaughter of animals; one of them proudly states:[81]

Our king killed very few animals.However, the edicts of Ashoka reflect more the desire of rulers than actual events; the mention of a 100 'panas' (coins) fine for poaching deer in royal hunting preserves shows that rule-breakers did exist. The legal restrictions conflicted with the practices freely exercised by the common people in hunting, felling, fishing and setting fires in forests.[81]

Contacts with the Hellenistic world

Mauryan ringstone, with standing goddess. Northwest Pakistan. 3rd Century BCE

Foundation of the Empire

Relations with the Hellenistic world may have started from the very beginning of the Maurya Empire. Plutarch reports that Chandragupta Maurya met with Alexander the Great, probably around Taxila in the northwest:- "Sandrocottus, when he was a stripling, saw Alexander himself, and we are told that he often said in later times that Alexander narrowly missed making himself master of the country, since its king was hated and despised on account of his baseness and low birth". Plutarch 62-4[82][non-primary source needed]

Reconquest of the Northwest (c. 317–316 BCE)

Chandragupta ultimately occupied Northwestern India, in the territories formerly ruled by the Greeks, where he fought the satraps (described as "Prefects" in Western sources) left in place after Alexander (Justin), among whom may have been Eudemus, ruler in the western Punjab until his departure in 317 BCE or Peithon, son of Agenor, ruler of the Greek colonies along the Indus until his departure for Babylon in 316 BCE.[citation needed]- "India, after the death of Alexander, had assassinated his prefects, as if shaking the burden of servitude. The author of this liberation was Sandracottos, but he had transformed liberation in servitude after victory, since, after taking the throne, he himself oppressed the very people he has liberated from foreign domination" Justin XV.4.12–13[83]

- "Later, as he was preparing war against the prefects of Alexander, a huge wild elephant went to him and took him on his back as if tame, and he became a remarkable fighter and war leader. Having thus acquired royal power, Sandracottos possessed India at the time Seleucos was preparing future glory." Justin XV.4.19[84]

Conflict and alliance with Seleucus (305 BCE)

A map showing the north western border of Maurya Empire, including its various neighboring states.

- "Always lying in wait for the neighbouring nations, strong in arms and persuasive in council, he [Seleucus] acquired Mesopotamia, Armenia, 'Seleucid' Cappadocia, Persis, Parthia, Bactria, Arabia, Tapouria, Sogdia, Arachosia, Hyrcania, and other adjacent peoples that had been subdued by Alexander, as far as the river Indus, so that the boundaries of his empire were the most extensive in Asia after that of Alexander. The whole region from Phrygia to the Indus was subject to Seleucus". Appian, History of Rome, The Syrian Wars 55[85]

Marital alliance

Chandragupta and Seleucus concluded a peace treaty and a marital alliance in 303 BCE. Chandragupta received vast territories, and in a return gesture, gave Seleucus 500 war elephants,[86][87][88][89][90] a military asset which would play a decisive role at the Battle of Ipsus in 301 BCE.[91] In addition to this treaty, Seleucus dispatched an ambassador, Megasthenes, to Chandragupta, and later Deimakos to his son Bindusara, at the Mauryan court at Pataliputra (modern Patna in Bihar state). Later, Ptolemy II Philadelphus, the ruler of Ptolemaic Egypt and contemporary of Ashoka, is also recorded by Pliny the Elder as having sent an ambassador named Dionysius to the Mauryan court.[92][better source needed]Mainstream scholarship asserts that Chandragupta received vast territory west of the Indus, including the Hindu Kush, modern-day Afghanistan, and the Balochistan province of Pakistan.[93][94] Archaeologically, concrete indications of Mauryan rule, such as the inscriptions of the Edicts of Ashoka, are known as far as Kandahar in southern Afghanistan.

| “ | "He (Seleucus) crossed the Indus and waged war with Sandrocottus [Maurya], king of the Indians, who dwelt on the banks of that stream, until they came to an understanding with each other and contracted a marriage relationship." | ” |

| “ | "After having made a treaty with him (Sandrakotos) and put in order the Orient situation, Seleucos went to war against Antigonus." | ” |

| — Junianus Justinus, Historiarum Philippicarum, libri XLIV, XV.4.15 | ||

Exchange of presents

Classical sources have also recorded that following their treaty, Chandragupta and Seleucus exchanged presents, such as when Chandragupta sent various aphrodisiacs to Seleucus:[42]- "And Theophrastus says that some contrivances are of wondrous efficacy in such matters [as to make people more amorous]. And Phylarchus confirms him, by reference to some of the presents which Sandrakottus, the king of the Indians, sent to Seleucus; which were to act like charms in producing a wonderful degree of affection, while some, on the contrary, were to banish love." Athenaeus of Naucratis, "The deipnosophists" Book I, chapter 32[95]

- "But dried figs were so very much sought after by all men (for really, as Aristophanes says, "There's really nothing nicer than dried figs"), that even Amitrochates, the king of the Indians, wrote to Antiochus, entreating him (it is Hegesander who tells this story) to buy and send him some sweet wine, and some dried figs, and a sophist; and that Antiochus wrote to him in answer, "The dry figs and the sweet wine we will send you; but it is not lawful for a sophist to be sold in Greece." Athenaeus, "Deipnosophistae" XIV.67[96]

Greek population in India

The Greek population apparently remained in the northwest of the Indian subcontinent under Ashoka's rule. In his Edicts of Ashoka, set in stone, some of them written in Greek, Ashoka relates that the Greek population within his realm was absorbed, integrated, and converted to Buddhism:- "Here in the king's domain among the Greeks, the Kambojas, the Nabhakas, the Nabhapamkits, the Bhojas, the Pitinikas, the Andhras and the Palidas, everywhere people are following Beloved-of-the-Gods' instructions in Dharma". Rock Edict Nb13 (S. Dhammika).[non-primary source needed]

The Kandahar Edict of Ashoka, a bilingual edict (Greek and Aramaic) by king Ashoka, from Kandahar. Kabul Museum. (Click image for translation).

- "Ten years (of reign) having been completed, King Piodasses (Ashoka) made known (the doctrine of) Piety (εὐσέβεια, Eusebeia) to men; and from this moment he has made men more pious, and everything thrives throughout the whole world. And the king abstains from (killing) living beings, and other men and those who (are) huntsmen and fishermen of the king have desisted from hunting. And if some (were) intemperate, they have ceased from their intemperance as was in their power; and obedient to their father and mother and to the elders, in opposition to the past also in the future, by so acting on every occasion, they will live better and more happily". (Trans. by G.P. Carratelli [1])[unreliable source?]

Buddhist missions to the West (c. 250 BCE)

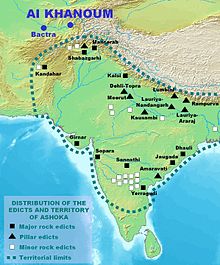

The distribution of the Edicts of Ashoka.[97]

Buddhist proselytism at the time of king Ashoka (260–218 BCE).

- "The conquest by Dharma has been won here, on the borders, and even six hundred yojanas (5,400–9,600 km) away, where the Greek king Antiochos rules, beyond there where the four kings named Ptolemy, Antigonos, Magas and Alexander rule, likewise in the south among the Cholas, the Pandyas, and as far as Tamraparni (Sri Lanka)." (Edicts of Ashoka, 13th Rock Edict, S. Dhammika).[non-primary source needed]

- "Everywhere within Beloved-of-the-Gods, King Piyadasi's [Ashoka's] domain, and among the people beyond the borders, the Cholas, the Pandyas, the Satiyaputras, the Keralaputras, as far as Tamraparni and where the Greek king Antiochos rules, and among the kings who are neighbors of Antiochos, everywhere has Beloved-of-the-Gods, King Piyadasi, made provision for two types of medical treatment: medical treatment for humans and medical treatment for animals. Wherever medical herbs suitable for humans or animals are not available, I have had them imported and grown. Wherever medical roots or fruits are not available I have had them imported and grown. Along roads I have had wells dug and trees planted for the benefit of humans and animals". 2nd Rock Edict[non-primary source needed]

Subhagasena and Antiochos III (206 BCE)

Sophagasenus was an Indian Mauryan ruler of the 3rd century BCE, described in ancient Greek sources, and named Subhagasena or Subhashasena in Prakrit. His name is mentioned in the list of Mauryan princes[citation needed], and also in the list of the Yadava dynasty, as a descendant of Pradyumna. He may have been a grandson of Ashoka, or Kunala, the son of Ashoka. He ruled an area south of the Hindu Kush, possibly in Gandhara. Antiochos III, the Seleucid king, after having made peace with Euthydemus in Bactria, went to India in 206 BCE and is said to have renewed his friendship with the Indian king there:"He (Antiochus) crossed the Caucasus and descended into India; renewed his friendship with Sophagasenus the king of the Indians; received more elephants, until he had a hundred and fifty altogether; and having once more provisioned his troops, set out again personally with his army: leaving Androsthenes of Cyzicus the duty of taking home the treasure which this king had agreed to hand over to him". Polybius 11.39[non-primary source needed]

Timeline

- 322 BCE: Chandragupta Maurya founded the Mauryan Empire by overthrowing the Nanda Dynasty.

- 317–316 BCE: Chandragupta Maurya conquers the Northwest of the Indian subcontinent.

- 305–303 BCE: Chandragupta Maurya gains territory from the Seleucid Empire.

- 298–269 BCE: Reign of Bindusara, Chandragupta's son. He conquers parts of Deccan, southern India.

- 269–232 BCE: The Mauryan Empire reaches its height under Ashoka, Chandragupta's grandson.

- 261 BCE: Ashoka conquers the kingdom of Kalinga.

- 250 BCE: Ashoka builds Buddhist stupas and erects pillars bearing inscriptions.

- 184 BCE: The empire collapses when Brihadnatha, the last emperor, is killed by Pushyamitra Shunga, a Mauryan general and the founder of the Shunga Empire.

Comments

Post a Comment